|

(1526-17th century)

|

The sepulchre of St Paul

the Hermit is devastated by the Ottomans

17th century Paper, engraving, 11.6 x 6.5 cm Inscription: Sepulchrum S. Pauli devastatur a Turcis / et Reliquiae incinerantur./ Das Grabmal des H. Pauli wird von dem Türcken / zerstöhret und dessen Heiligthum verbrant./ 23. / Budapest, Hungarian National Museum, inv. no: 69/1951. Gr. The remains of St Paul the Hermit were taken to Buda in 1381, after the relic had been asked by King Lajos I on the occasion of the peace treaty with the Republic of Venice. It was placed in the Chapel of Buda Castle, then got to the central monastery of the Paulite order in Budaszentlôrinc. His cult lasted till the end of the 18th century. The missal of the only Hungarian-founded order was published in Basel in 1490, but another copy was made for the order of George Martinuzzi in 1537, which is preserved in the collection of the National Széchenyi Library in Budapest. The biography of St Paul the Hermit was published in Venice in 1511, but was illustrated only by a few woodcuts of simple composition. (It is now in the collection of the Ervin Szabó Library of Budapest.) This composition was originally a book illustration, a characteristic example of the saint’s cult in the Baroque period. On the left side of the composition an open hall – perhaps the interior of a church – can be seen. The pillars, the wall surfaces and columns are richly ornamented. The coffin of the saint is broken by the Ottomans’ axes, while monks are being killed in the foreground. Burning buildings appear in the background. Iconographic types of graphic series illustrating the lives of saints often choose composition types to represent everyday scenes, like in this case. |

|

King Matthias triumphs over

the Ottomans through the mediation of St Paul the Hermit

18th century Paper, engraving, 11.6 x 6.5 cm Inscription: Mathias Corvinus Hungariae Rex op S Pauli / Turcas profligat. / Mathias König in Hungarn sieget über die Türcken / durch beystand des H. Pauli. / 18. Budapest, Hungarian National Museum, inv. no: 68/1951. Gr. This composition was also a book illustration. In the foreground there is a battle scene, with the fighting figure of King Matthias on horseback in the middle. In the right upper corner the figure of St Paul appears surrounded by rays of light. The composition imitates the Baroque type of battle scenes, similar pieces were the favorite subjects of graphic works and paintings as well. |

|

Rudolf Hoffmann (active

in the 1840’s-50’s):

Martin Luther Mid-19th century Paper, lithography; 50 x 36.5 cm Inscription: LUTHER. Mit Vorbehalt aller Rechte Vervielfaltigung / Druck-Verlag u. Reigenthum v. PATERNO Cie Wien. Signed on the right below: Rud Hoffmann Budapest, Hungarian National Museum, inv. no: 58.1394 The three-quarter portrait represents Martin Luther wearing a gown and a fur-trimmed cloak, holding a book (the Bible?) in his right hand. The lithography is a characteristic composition of the mid-19th century, lacking details or background, only the person represented is significant, most importantly striving for authenticity and the exactness of the portrait. Rudolf Hoffmann was active as a lithographist and miniature painter in Vienna, his works were first exhibited in 1843. He made a large number of lithography copies of the works of famous painters, for example, of the compositions of József Borsos. He made a series about famous people for the institute of A. Paterno, but only a few of them are known today. The Luther-portrait might have been a piece of the series. |

|

Lenhardt,

Sámuel (Poprád, 1817 – Pest, 1840)

John Calvin C. 1840 Paper, engraving; 46 x 32 cm Budapest, Hungarian National Museum, inv. no: 6277 Inscription: CALVINUS JÁNOS

Ezen Nagy Ember igaz Tisztelôinek ajánlva.

The tympanum symbolising the Holy Trinity is held by two columns and two pillars. Calvin himself stands below the canopy-like structure. The columns, the tympanum and the stairs are covered with inscriptions. The full-length standing portrait most probably imitates an earlier representation. Lenhardt was studying in Vienna between 1814 and 16, his masters were Lampi, Fischer and Höfel. He had been working in Pest from 1817 on, had a workshop in Hatvani street. His oeuvre is very rich and versatile. Among others he made portraits, vedutas, maps, antiquities, writing patterns. Most of his works were published in the periodical Tudományos Gyûjtemény (Scientific Collection), but he also made illustrations for the pocket-book Aurora. He was one of the most outstanding graphic artist in Hungary in the first half of the 19th century. |

|

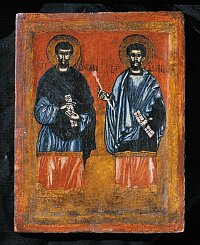

Serbian painter

Icon of St Cosmas and Damian 16th century Oil, wooden panel; 26 x 20.5 cm Esztergom, Christian Museum, inv. no: 56.582 The icon got to the Ramboux collection in Cologne from a church near Belgrade. Then it became an object of the Ipolyi collection. The veneration of the doctor saints was widespread both in the Eastern and Western Church. Bibliography: Magyarország mûemléki toporgáfiája, ed. by Genthon, I., Budapest 1948, p. 60; Ruzsa, Gy., A Keresztény Múzeum ikonjai, exhibition catalogue, Esztergom 1978, n. 2. |

| JACOB HOEFNAGEL

(Antwerp, 1575 – Munich, around 1630)

The fort of Buda 1617 Paper, engraving 32 x 48 cm Esztergom, Christian Museum, inv. no: Gr. 4681 The view of the fort of Buda

together with the Pasha of Buda is an imaginary representation made during

the period of Ottoman rule. The engraving is an illustration of the work

of Braun-Hogenberg. The inscription, claiming it was published by Georg

Hoefnagel, is erroneous.

|

|